By

Long-lasting, icy cirrus clouds filled with Saharan dust covered many parts of the continent in March.

In March 2022, several large storms carried clouds of Saharan dust to Europe. One of them also brought long-lasting, high-altitude cirrus clouds infused with dust, which led to extensive cloud cover—from Iberia to the Arctic—for more than a week. It was an unusual type of storm that scientists have only recently come to understand. Called a dust-infused baroclinic storm (DIBS), its hallmarks are icy clouds permeated with dust.

In mid-March, an atmospheric river of Saharan dust was entrained by a DIBS and lifted into the troposphere, reaching altitudes up to 10 kilometers (6 miles). The dust acted as nucleation particles for ice, leading to the formation of icy high-altitude, dust-infused cirrus clouds. They persisted for nearly a week and covered large parts of Europe and Asia.

“Actually, two DIBS were formed,” said Mike Fromm, a meteorologist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. “The fact that the dust river fed two separate DIBS makes this notable” as it is more common to see a single storm arise from an influx of dust.

The first storm started on March 15, 2022, over north central Europe and spread from Poland, Czechia, and Austria south to the eastern Mediterranean. This was also unusual, Fromm said, as there is “usually a direct connection of a DIBS to its dry dust source, closer to the desert itself.”

On March 16, a second storm followed the classic pattern, spinning up closer to the source of the dust in Africa. The large, widespread dust cloud continued moving north over Europe toward Scandinavia and the Artic Ocean. It then moved east over northern Russia before taking an anticyclonic turn and curving back down into Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region on March 20.

In the above image, acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite on March 17, 2022, the cloud tops exhibit a dimpled appearance. “We still don’t know why that happens,” Fromm said, “but it is peculiar to DIBS.”

Analysis of the mid-March storms by Colin Seftor, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, showed that much of the dust was circulating at the top of the cloud deck. “This means there is enough dust at the cloud tops to give the normally white clouds a dusty tinge, ergo the ‘infused’ part of the name,” Fromm said. “In the DIBS, the dust and storm cloud are one.”

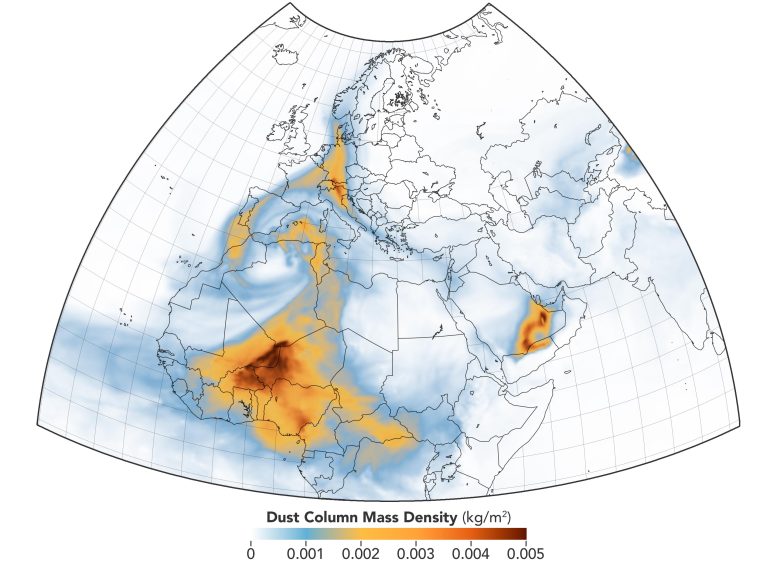

The map above shows a model of the dust movement on March 17 based on the Goddard Earth Observing System Model, Version 5 (GEOS-5).

The high, dusty cloud layers produced by DIBS have been observed to travel around the world, Fromm said, and can sometimes be mistaken for volcanic ash that could affect flight paths. They have local effects as well. The dust that gets drawn up into them tends to linger after the clouds evaporate, Fromm added. Also, longer-lasting cirrus clouds can affect forecasts of temperature and precipitation.

In late March, yet another large dust storm started making its way north carrying Saharan dust over the Mediterranean and Europe. Although the latest storm appears to be similarly large, it may not be as long-lasting, Seftor said. “Two large [storms] like this almost back-to-back is somewhat unusual, but the weather patterns over northern Africa and Europe during the spring seem to be more conducive to producing dust storms that reach Europe than at other times of the year.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, and GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC.