The remains of numerous individuals unearthed on the former site of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist, taken during the 2010 excavation. Credit: Cambridge Archaeological Unit/St John’s College

A major research project has produced a collection of ‘bone biographies’ that narrate the lives of individuals from medieval Cambridge, as interpreted from their skeletal remains. These biographies shed light on the daily experiences of people during the period of the Black Death and its aftermath.

The work is published alongside a new study investigating medieval poverty by examining remains from the cemetery of a former hospital that housed the poor and infirm. University of Cambridge archaeologists analyzed close to 500 skeletal remains excavated from burial grounds across the city, dating between the 11th and 15th centuries. Samples came from a range of digs dating back to the 1970s.

The latest techniques were used to investigate diets, DNA, activities, and bodily traumas of townsfolk, scholars, friars, and merchants. Researchers focused on sixteen of the most revealing remains that are representative of various “social types”.

The full “osteobiographies” are available on a new website launched by the After the Plague project at Cambridge University.

A photograph of part of the face of project number 766 (‘Dickon’) who died of plague in Cambridge during the Black Death. Credit: After the Plague

“An osteobiography uses all available evidence to reconstruct an ancient person’s life,” said lead researcher Prof John Robb from Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology. “Our team used techniques familiar from studies such as Richard III’s skeleton, but this time to reveal details of unknown lives – people we would never learn about in any other way.”

“The importance of using osteobiography on ordinary folk rather than elites, who are documented in historical sources, is that they represent the majority of the population but are those that we know least about,” said After the Plague researcher Dr Sarah Inskip (now at University of Leicester).

The project used a statistical analysis of likely names drawn from written records of the period to give pseudonyms to the people studied.

“Journalists report anonymous sources using fictitious names. Death and time ensure anonymity for our sources, but we wanted to them to feel relatable,” said Robb.

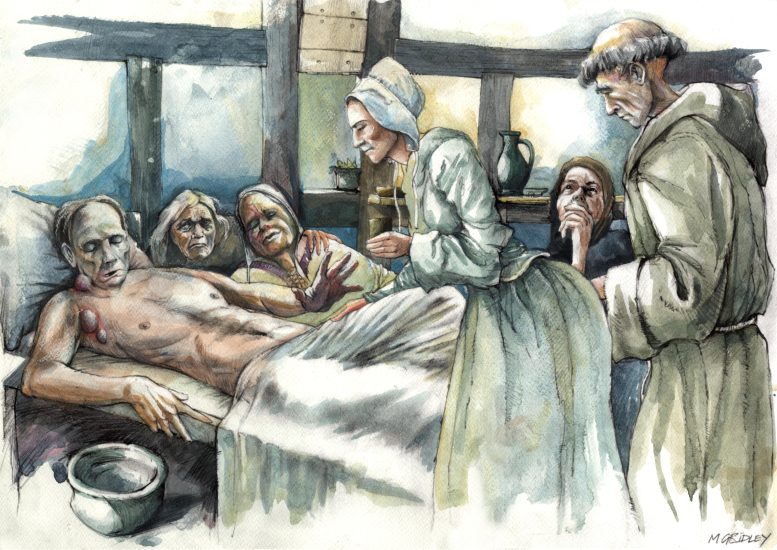

An illustration of project number 766 (‘Dickon’) based on the osteobiography generated through analyses of remains excavated from All Saints cemetery. ‘Dickon’ was born in Cambridge between 1289 and 1317, and died around 1349. He probably lived through the Great Famine of 1315-1320 as a child, which may have stunted his growth. He became a muscular man who stood at 5ft 2in. He had worn-down front teeth, probably as a result of relying on them to chew due to lost molars. ‘Dickon’ most likely died in the first wave of Black Death, and his skeleton contains plague DNA. Credit: Mark Gridley/After the Plague

Meet 92 (‘Wat’), who survived the plague, eventually dying as an older man with cancer in the city’s charitable hospital, and 335 (‘Anne’), whose life was beset by repeated injuries, leaving her to hobble on a shortened right leg.

Meet 730 (‘Edmund’), who suffered from leprosy but – contrary to stereotypes – lived among ordinary people, and was buried in a rare wooden coffin. And 522 (‘Eudes’), the poor boy who grew into a square-jawed friar with a hearty diet, living long despite painful gout.

Inside the medieval benefits system

The website coincides with a study from the team published in the journal Antiquity, which investigates the inhabitants of the hospital of St. John the Evangelist.

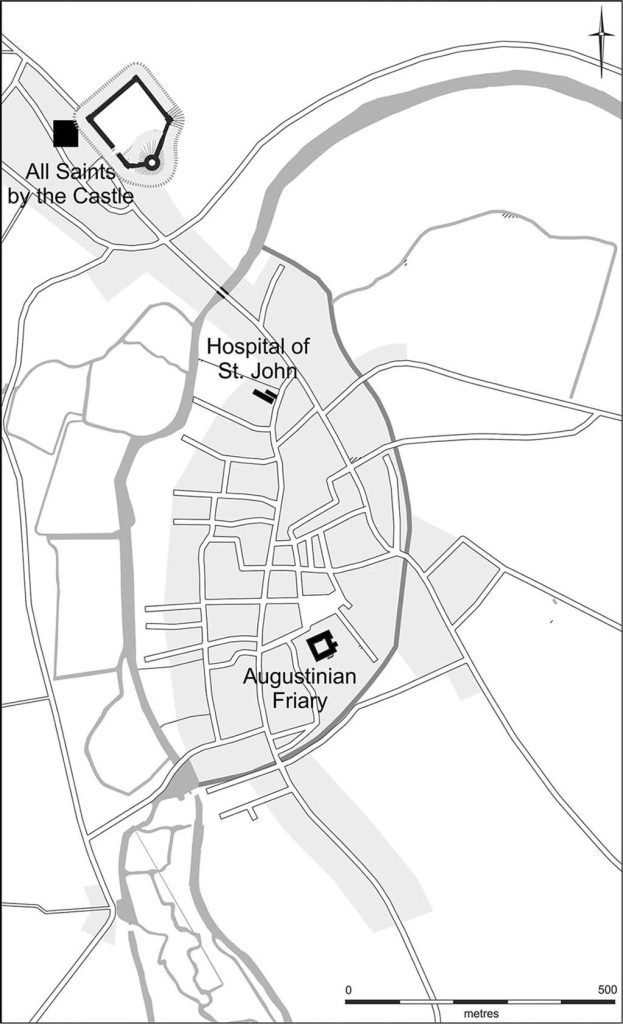

Founded around 1195, this institution helped the “poor and infirm”, housing a dozen or so inmates at any one time. It lasted for some 300 years before being replaced by St. John’s College in 1511. The site was excavated in 2010.

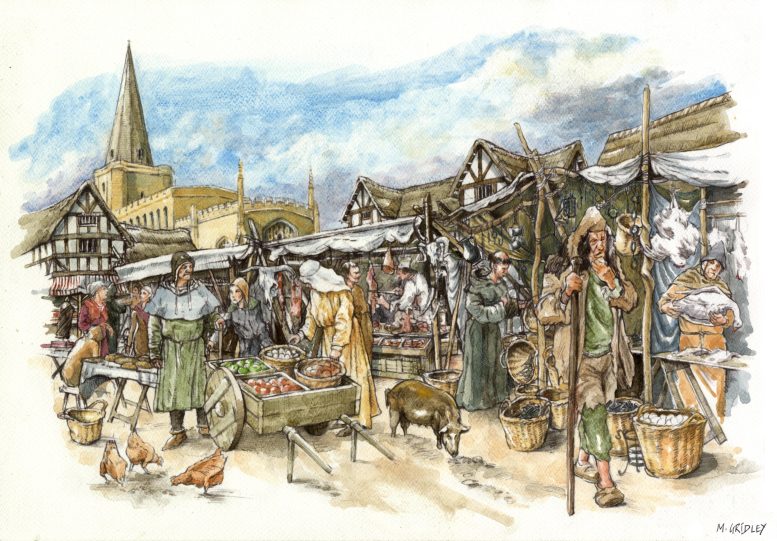

“Like all medieval towns, Cambridge was a sea of need,” said Robb. “A few of the luckier poor people got bed and board in the hospital for life. Selection criteria would have been a mix of material want, local politics, and spiritual merit.”

The study gives an inside look at how a “medieval benefits system” operated. “We know that lepers, pregnant women, and the insane were prohibited, while piety was a must,” said Robb. Inmates were required to pray for the souls of hospital benefactors, to speed them through purgatory. “A hospital was a prayer factory.”

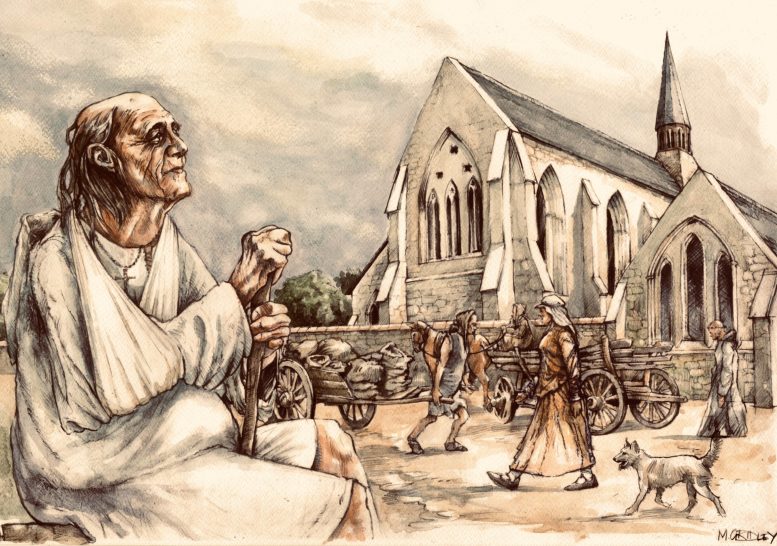

An illustration of project number 92 (‘Wat’) based on the osteobiography generated through analyses of remains excavated from the main cemetery of the hospital of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge. ‘Wat’ as an older man, likely born between 1316-1347 and died between 1375-1475. He lived through the Black Death, perhaps ending up in St. John the Evangelist after becoming impoverished in old age. He died in the hospital while sick with cancer. Credit: Mark Gridley/After the Plague

Molecular, bone and DNA data from over 400 remains in the hospital’s main cemetery shows inmates to be an inch shorter on average than townsfolk. They were more likely to die younger and show signs of tuberculosis.

Inmates were more likely to bear traces on their bones of childhoods blighted by hunger and disease. However, they also had lower rates of bodily trauma, suggesting life in the hospital reduced physical hardship or risk.

Children buried in the hospital were small for their age by up to five years’ worth of growth. “Hospital children were probably orphans,” said Robb. Signs of anemia and injury were common, and about a third had rib lesions denoting respiratory diseases such as TB.

As well as the long-term poor, up to eight hospital residents had isotope levels indicating a lower-quality diet in older age, and may be examples of the “shame-faced poor”: those fallen from comfort into destitution, perhaps after they became unable to work.

“Theological doctrines encouraged aid for the shame-faced poor, who threatened the moral order by showing that you could live virtuously and prosperously but still fall victim to twists of fortune,” said Robb.

Members of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at work on the excavation of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist in 2010. Credit: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

The researchers suggest that the variety of people within the hospital – from orphans and pious scholars to the formerly prosperous – may have helped appeal to a range of donors.

Finding the university scholars

The researchers were also able to identify some skeletons as probably those of early university scholars. The clue was in the arm bones.

Almost all townsmen had asymmetric arm bones, with their right humerus (upper arm bone) built more strongly than their left one, reflecting tough working regimes, particularly in early adulthood.

However, about ten men from the hospital had symmetrical humeri, yet they had no signs of a poor upbringing, limited growth, or chronic illness. Most dated from the later 14th and 15th century.

An illustration of the marketplace in medieval Cambridge by the artist Mark Gridley. Credit: Mark Gridley/After the Plague

“These men did not habitually do manual labor or craft, and they lived in good health with decent nutrition, normally to an older age. It seems likely they were early scholars of the University of Cambridge,” said Robb.

“University clerics did not have the novice-to-grave support of clergy in religious orders. Most scholars were supported by family money, earnings from teaching, or charitable patronage.

“Less well-off scholars risked poverty once illness or infirmity took hold. As the university grew, more scholars would have ended up in hospital cemeteries.”

Isotope work suggests the first Cambridge students came mainly from eastern England, with some from the dioceses of Lincoln and York.

Map of medieval Cambridge with the locations of the three main burial sites used in the After the Plague research project. Credit: V. Herring/Antiquity

Cambridge and the Black Death

Most remains for this study came from three sites. In addition to the Hospital, an overhaul of the University’s New Museums Site in 2015 yielded remains from a former Augustinian Friary, and the project also used skeletons excavated in the 1970s from the grounds of a medieval parish church: ‘All Saints by the Castle’.

The team laid out each skeleton to do an inventory, and then took samples for radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis. “We had to keep track of hundreds of bone samples zooming all over the place,” said Robb

In 1348-9 the bubonic plague – Black Death – hit Cambridge, killing between 40-60% of the population. Most of the dead were buried in town cemeteries or plague pits such as one on Bene’t Street next to the former friary.

However, the team has used the World Health Organization’s methods of calculating “Disease Adjusted Life Years” – the years of human life and life quality a disease costs a population – to show that bubonic plague may have only come in tenth or twelfth on the risk rundown of serious health problems facing medieval Europeans.

“Everyday diseases, such as measles, whooping cough, and gastrointestinal infections, ultimately took a far greater toll on medieval populations,” said Robb.

“Yes, the Black Death killed half the population in one year, but it wasn’t present in England before that, or in most years after that. The biggest threats to life in medieval England, and in Western Europe as a whole, were chronic infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.”

Reference: “Pathways to the medieval hospital: collective osteobiographies of poverty and charity” by Sarah Inskip, Craig Cessford, Jenna Dittmar, Alice Rose, Bram Mulder, Tamsin O’Connell, Piers D. Mitchell, Christiana Scheib, Ruoyun Hui, Toomas Kivisild, Mary Price, Jay Stock and John Robb, 1 December 2023, Antiquity.

DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2023.167