NASA’s airborne Lunar Spectral Irradiance, or air-LUSI, flew aboard NASA’s ER-2 aircraft from March 12 to 16 to accurately measure the amount of light reflected off the Moon. Reflected moonlight is a steady source of light that researchers are taking advantage of to improve the accuracy and consistency of measurements among Earth-observing satellites.

“The Moon is extremely stable and not influenced by factors on Earth like climate to any large degree. It becomes a very good calibration reference, an independent benchmark, by which we can set our instruments and see what’s happening with our planet,” said air-LUSI’s principal investigator, Kevin Turpie, a research professor at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The air-LUSI flights are part of NASA’s comprehensive satellite calibration and validation efforts. The results will compliment ground-based sites such as Railroad Valley Playa in Nevada, and together will provide orbiting satellites with a robust calibration dataset.

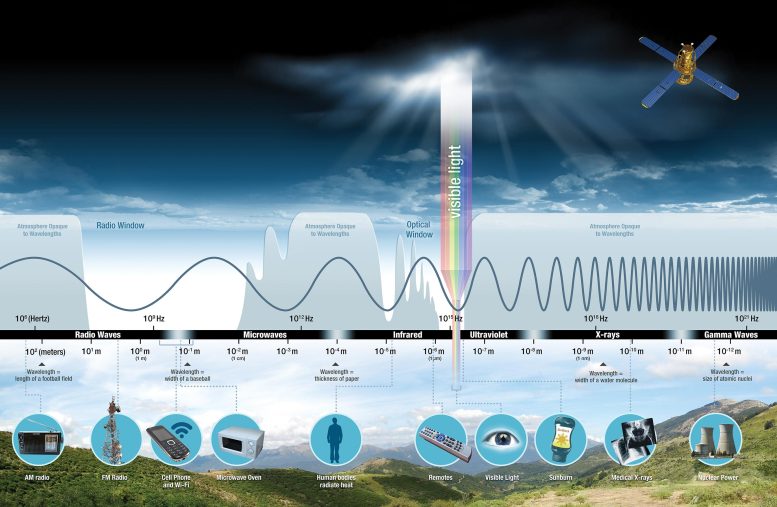

NASA has more than 20 Earth-observing satellites that give researchers a global perspective on the interconnected Earth system. Many of them measure light waves reflected, scattered, absorbed, or emitted by Earth’s surface, water and atmosphere. This light includes visible light, which humans see, as well as invisible ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths, and everything in between. Like musical instruments in an orchestra, the individual satellite instruments need to be “in tune” with each other in order for researchers to get the most out of their data. By using the Moon as a “tuning fork,” scientists can more easily compare data from different satellites to look at global changes over long periods of time.

This electromagnetic spectrum shows how energy travels in waves; Humans can only see visible light, but the entire spectrum is used by NASA instruments to observe Earth and more. Credit: NASA

That’s where air-LUSI comes in. Developed in partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Geological Survey and McMaster University, air-LUSI is a telescope that measures how much light is reflected off the lunar surface to assess the amount of energy Earth-observing satellites receive from moonlight. It was mounted aboard the ER-2 aircraft managed by and flying out of NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Palmdale, California. The ER-2 is a high-altitude aircraft that flew at 70,000 feet, above 95% of the atmosphere, which can scatter or absorb the reflected sunlight. This allowed air-LUSI to collect very accurate, NIST traceable measurements that are analogous to those a satellite would make from orbit. In order to improve the accuracy of lunar reflectance models, air-LUSI measurements are accurate with less than 1% uncertainty. During the March flights, air-LUSI measured the Moon for four nights just before a full Moon.

This airborne approach has the advantage of studying moonlight during different phases of the Moon while being able to bring the instrument back between flights for evaluation, maintenance, and, if necessary, repair.

Shown is the air-LUSI telescope positioned to measure a simulated Moon in a laboratory for testing and calibration before and after the flight campaign. Credit: Kevin Turpie

Making Improvements for Better Accuracy

The air-LUSI spectrometer is hermetically sealed within an enclosure that keeps the instrument constantly at sea level temperature and pressure. Light collected by a telescope enters an integrating sphere which directs the light to the spectrometer, which is an instrument that measures variances of light waves. The air-LUSI first flew in similar flights in November 2019. Since then, the air-LUSI team has continued to improve the instrument’s accuracy.

The team improved the internal monitor so they can better check instrument accuracy over a greater range of wavelengths, from the ultraviolet to the near infrared. They were also able to redesign the integrating sphere to remove small effects of changing temperature.

“This will help the instrument make measurements with the more than 99% accuracy levels we’re looking for,” said Turpie.

Making these changes was challenging. Delays from the COVID-19 pandemic caused the chief engineer, who was working on the instrument updates and repairs, to develop a new remote work plan. Both he and the principal investigator received special permission to have parts delivered directly to their homes so they could work on the instrument and be prepared for the 2022 flights.

Using the Moon as a Common Standard

The data from 2019 and 2022 together has the potential to assist scientists in making Earth-observing satellite data in the ultraviolet to near-infrared range more consistent. In addition, the common Moon standard would make it easier to compare and fine-tune current and future satellite observations. NASA’s upcoming Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission is planning on using the Moon as a common benchmark to make its observations more accurate and inter-consistent with other satellite measurements of Earth. Over the next decade, PACE and the future orbiting sensors of NASA’s Earth System Observatory will help create a more cohesive picture of our planet.

“Having a common calibration source outside of the Earth will help us reach this objective,” said Turpie. “Once air-LUSI measurements are used to improve the accuracy of the total amount of light coming from the Moon, we can take extensively more accurate measurements of Earth using current and future space-borne observatories.”